When the Nobel Prize in Literature is announced, I like to read the winner’s book and decide if I agree that the work deserves the prize. In 2023, the winner was Jon Fosse of Norway, primarily known as a playwright in his country. I usually do not like innovations in mechanics or gratuitous experimentations with structure and writing style. In this case, I was pleasantly surprised by Fosse’s writing style. The book is almost 700 pages in English translation from the Norwegian. If run-on sentences, no periods, and no paragraphs except in dialogue put you off, you probably will not read long enough to appreciate the merits of this novel.

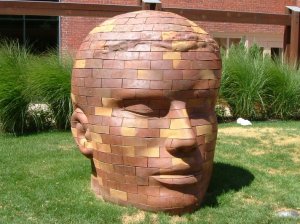

It took me less than twenty pages to become infatuated with the cadence of the run-ons that flow effortlessly in mimicry of gentle waves as Asle, the main character, drifts from the present into the past on a sea of memory where all time merges. Asle constantly interjects the phrase “I think” in his stream of consciousness, underscoring the fact that the novel is a long philosophical treatise on the universal questions of love, mortality, art, and the existence of God. Asle’s musings are a study in contrasts. It is contrapuntal, always weighing one point of view against another. Asle is an old painter who meditates on the purpose of all art and the rationale behind his paintings. He is obsessed with dark and light. The invisible and the visible haunt him. He strives to create “shining darkness” in his paintings.

The novel encompasses seven days in Asle’s life in a way reminiscent of Joyce’s Ulysses covering one day in Dublin. It is the week before Christmas, and the novel ends significantly on Christmas Eve. Asle drives back and forth from his small village to a city where his paintings have been exhibited in a gallery over his long career. Many similarities and doublets occur. For instance, his dead wife’s name was Ales, an inversion of his name. He has an alcoholic friend, who is also named Asle and is a painter. After he finds his friend passed out in the snow, he takes him to the hospital. I frequently wondered if the second Asle was real or imaginary. The second Asle is the antithesis of the narrator Asle who stops drinking. The alcoholic Asle has three unsuccessful marriages, but the narrator Asle never remarries after his beloved wife dies. The invisible comes to life as he visualizes scenes of his past life with Ales wherever he goes. Ales is religious. She converts Asle to Catholicism and saves him from the alcoholism that would have destroyed his painting career. Each of the seven sections of the novel ends with Asle reciting Catholic prayers in Latin and in English. Over seven days, he ponders philosophical and religious questions.

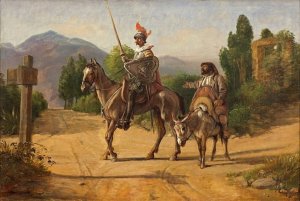

On the first day, he paints what his neighbor calls St. Andrew’s Cross—a brown line and a purple line that intersect. Asle vacillates about whether the painting is finished or not, and he really does not want to give it away as a Christmas present or sell it. This image and the two colors carry a significance over the seven days. The brown line suggests Asle, and the purple line Ales. Integral to the novel is the intersection of art and the divine. The cross symbolizes the conjunction of events, interconnections, and the meeting of opposites. There are two sides to every question, and Asle, the deep thinker, continually juxtaposes ideas.

Asle’s ruminations are striking, beautiful, and eloquent: I really have withdrawn into the wordless prayer of painting . . . because the darker I am the closer God is . . .the human being is a continuous prayer. These are just three examples of the gorgeous prose in this novel. A reader who wants to delve beneath surface reality will love Jon Fosse’s writing and the extraordinary character of The Thinker he portrays in Septology.

“Invisible darkness” is a key phrase that Asle often repeats. The essence of Asle’s belief system is that art has a religious purpose and that paradox is inherent in everything. The cross is the symbol of the paradox. That is why there are so many juxtapositions of thought, characters, and opinions in Septology. The suffix -ology means the study of something, and sept indicates the seven-day discourse. I love this book because Asle is the perpetual student of art and philosophy. Literature that endures over the centuries, at its essence, teaches something about the human condition. Jon Fosse does it superbly.

February 4, 2024