In colonial Peru an extraordinary number of women lived in convents. At their peak in the seventeenth century, one fifth of Lima’s female population lived in its thirteen nunneries. During their rise during the second half of the sixteenth century, the great convents provided the logical refuge for women seeking to escape male domination. The two convents in Cuzco, Santa Clara and Santa Catalina, were typical of these little cities within a city modeled after European convents in Belgium, France and Spain. Despite their establishment under the male authority of their religious orders, the women pursued independent lives behind the convent walls, enjoying theatrical performances, music, gardening, needlework, entertaining guests, and even rearing babies left at the convent door as their own. Many of the nuns were wealthy, upper class women, who brought both their large dowries and their personal servants to the convent.

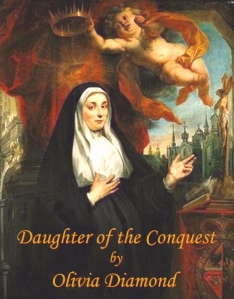

From reading about convent social life, the comings and goings of visitors, and the luxurious quarters of the wealthy nuns, some even dwelling in separate little cottages; I realized that entering the nunnery would be a desirable choice for an independent-minded woman like my central character in Daughter of the Conquest, the third novel in my historical trilogy. Far from restricting her range in a story, the convent would extend her possibilities as a woman. To escape her unhappy marriage, Mirasol flees to the convent of Santa Clara. Life there is a far cry from the cloister of austere cells that I had thought typified a nun’s existence before my research into the great convents of the colonial period. Mirasol’s retreat from secular life is not total, for as abbess of Santa Clara, Mirasol plays an important role in Cuzco society, wielding political and economic power unlikely for a married woman in colonial society.

Placing my character in the convent also allowed me to develop how colonial rulers carried out Christianization and the acculturation of the indigenous Incan royalty into Spanish social structure. The Catholic Church served to amalgamate elements of the native culture into the context of Christianity and of western European society. Now that the sword had claimed the land for Spain, the cross was enlisted to win souls for Christ. The setting of the convent of Santa Clara helped both to create a strong female central character and to dramatize the process of colonization in Peru, part of the former vast empire of the Incas.

The outlets for women were indeed narrow in earlier centuries, but the convent in Christendom afforded a bastion and a refuge for women. Furthermore, it was a place that promoted and facilitated the education of women. For a woman with a thirst for learning, books were available there to expand her knowledge. A girls’ school was usually associated with the great convents. After graduation, the girls could choose to enter the convent or to marry. Marriage was a dangerous option, offering a good chance of an early death in childbirth. Rape was always a possibility when war rather than peace was the norm. With the odds against women, is it so surprising that as many as twenty percent of the female population chose to take the nun’s veil?

Especially, when babes in baskets found on the convent door step meant no nun’s maternal instinct need go unsatisfied.