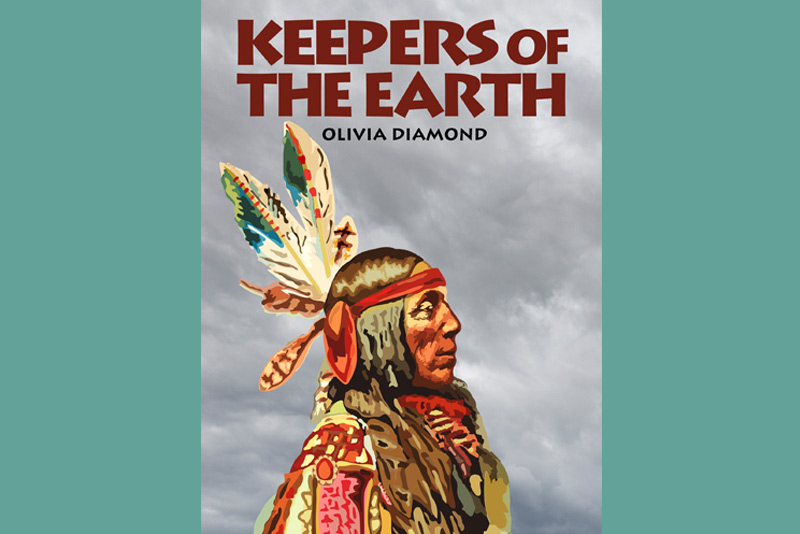

My interest in Native-American culture, not only North American but also South American, goes back a long way. I locate the germ of my idea for my latest novel Keepers of the Earth, in which my fictional character Running Wolf leads a band of Salish Indians into seclusion, from reading in the early 1970s Ishi in Two Worlds by Theodora Kroeber. Ishi emerged from hiding in the Sierra Nevada Mountains on August 29, 1911, the sole survivor of his family. Alfred and Theodora Kroeber, University of California anthropologists, worked with Ishi to record his culture and language. I was so fascinated with Ishi that I read all I could find about him and watched several documentaries about him. Only after I finished writing my novel, did I realize that I had drawn Ishi from the recesses of my memory bank.

The subject of influences is a major part of the study of authors and comparative literature. The question of whether any work of literature is entirely original is a valid one. We are receptors of influences because we are sentient beings. Years ago, as a college student, I read T. S. Eliot’s essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” I have reread it many times since. In his essay, Eliot argues that a writer inevitably imbibes history. Consequently, the writer’s sense of history is essential to the art he creates. A historical sense is what makes art transcend the purely personal. The artist has fused his personal experience with a knowledge of the past. In this sense a piece of art cannot be termed strictly original. I have heard that some writers avoid reading any novels similar to the one they are working on at the time because they do not want to be unconsciously influenced by another author’s treatment of the subject. They want their novel to be an unadulterated product of their personal creativity.

Keepers of the Earth is not my first work that centers on indigenous American culture. In 1992 the Illinois composer Fred Hubbell asked me to write the lyrics for his choral piece “Sinnissippi Saga.” I wrote a series of poems centering around the Sauk, Fox, and Potawatomi tribes who occupied that part of the Mississippi Valley. Parts of my poems were used in the score and were performed in Rockford, Illinois, that year. The phrase “keepers of the earth” is repeated in an Indian chant used in the production. I must have stored the phrase in the back of my brain because I knew it was the right title for my novel about the Salish of Montana. My study of Native-American dance chants also remained in my subconscious. Short repeated lines and the slight variation of lines otherwise having the same cadence typify these songs. And in Keepers of the Earth, I created new Native-American chants that accompany the singing and dancing that were part of major events in the life of the Salish.

Native-American characters also appear in my other novels. In The Pluperfect Phantom, Nuscotomeg or Mad Sturgeon arises from the past to subdue the ghost of the serial killer plaguing characters in the present. The old storyteller, Uncle Johnny in The Wheels of Being, recounts Indian legends to two children. I first developed my research into the Incan civilization of South America in my collection of narrative poetry, Land of the Four Quarters, which depicts the Spanish conquest and colonization of Peru and Ecuador. At my husband’s suggestion, I transformed the material into three novels, Voice of Stone, Conquistadora, and Daughter of the Conquest.

I have always been overcome with sadness and shame whenever I have read the history of the European extermination of the native populations and the destruction of their traditions. In writing Keepers of the Earth, I wanted to answer the question: What if a small band of Salish in northwest Montana retreated from the encroachments of white society and managed to maintain their traditional way of life for sixty years in a remote area of the Rocky Mountains?

Jane Smiley, in Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, writes: “When I was writing The Greenlanders, it was obvious to me that all novels were historical novels, patiently reconstructing some time period or another, recent or distant.” The evolution of my writing synthesizes what I have gleaned from history. My narrative combines fictional and historical characters. The historical fiction, which relates what could be called alternative history, envisions a series of events that might have happened and carries a relevance for today. Almost all the Salish characters are imagined. Some of the historical characters who enter the novel are Father Pierre De Smet and other Jesuit missionaries. Actual historical events, such as the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, are included. The natural disasters occurring today seem to be the earth’s rebellion against colonial exploitation of the environment, its resources, and its people.

Colonialism and its aftereffects continue to influence the course of contemporary events. The message that all people must unite to save the environment underscores my narrative. Native-American spirituality can tell us how to do this and how we can all start acting less divisively. Walls and fences do not build good neighbors. They establish separation. Divide and conquer have been the watchwords for too long. Language has been a tool of colonial destruction, for the colonists systematically worked to eradicate indigenous languages, and in doing so, destroyed the cultures of the peoples they conquered. This is also the story I tell in Keepers of the Earth.